So, after diving into the Review Board extension code, I hit a little snag.

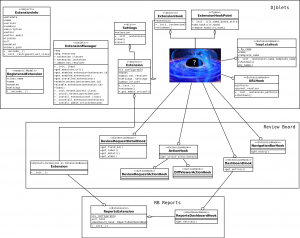

It turns out I never learned about Python metaclasses. And the extension code in Djblets / Review Board uses them. In the map I made of the Review Board extension code, I represented my confusion with an image of some kind of quantum-divide-by-zero implosion.

I’ll get to the why for metaclasses in a second. First, I’ll demonstrate how it’s currently being used in the code.

The Way Things Are

This snippit is from the Djblets library, in the extensions folder, in base.py:

... class ExtensionHook(object): def __init__(self, extension): self.extension = extension self.extension.hooks.add(self) self.__class__.add_hook(self) def shutdown(self): self.__class__.remove_hook(self) class ExtensionHookPoint(type): def __init__(cls, name, bases, attrs): super(ExtensionHookPoint, cls).__init__(name, bases, attrs) if not hasattr(cls, "hooks"): cls.hooks = [] def add_hook(cls, hook): cls.hooks.append(hook) def remove_hook(cls, hook): cls.hooks.remove(hook) ...

And here are those classes being used in the Review Board extension directory, where it defines its hooks:

... class DashboardHook(ExtensionHook): __metaclass__ = ExtensionHookPoint def get_entries(self): raise NotImplemented class NavigationBarHook(ExtensionHook): """ A hook for adding entries to the main navigation bar. """ __metaclass__ = ExtensionHookPoint def get_entry(self): """ Returns the entry to add to the navigation bar. This should be a dict with the following keys: * `label`: The label to display * `url`: The URL to point to. """ raise NotImplemented ...

The idea here is that, if someone wanted to write an extension, they could add a hook to the navigation bar by subclassing the hooks, like so:

(from the rbreports prototype extension)

...

class ReportsDashboardHook(DashboardHook):

def get_entries(self):

return [{

'label': 'Reports',

'url': settings.SITE_ROOT + 'reports/',

}]

class ReportsExtension(Extension):

is_configurable = True

def __init__(self):

Extension.__init__(self)

self.url_hook = URLHook(self, patterns('',

(r'^reports/', include('rbreports.urls'))))

self.dashboard_hook = ReportsDashboardHook(self)

...

So you can see the __metaclass__ thing up there in the DashboardHook. DashboardHook subclasses ExtensionHook, and has ExtensionHookPoint as a metaclass.

Why? And what is a metaclass anyways? Why is this useful at all?

Well, luckily, I think I’ve figured it out.

Behold – Metaclasses

Metaclasses are deeper magic than 99% of users should ever worry about. If you wonder whether you need them, you don’t (the people who actually need them know with certainty that they need them, and don’t need an explanation about why).

— Python Guru Tim Peters

There are plenty of resources available regarding Python’s metaclasses. And I ended up reading a ton of them trying to figure out just what the hell metaclasses actually do.

As it turns out, the best explanation I got was from Wikipedia:

In object-oriented programming, a metaclass is a class whose instances are classes. Just as an ordinary class defines the behavior of certain objects, a metaclass defines the behavior of certain classes and their instances.

In particular, check out their example on Cars. That, for me, more or less set the record straight on how metaclasses are used.

But why does Review Board use them when defining those hooks, like DashboardHook?

Why?

Forget the metaclasses for just a second.

Something is missing from that code that I posted up.

I’ll pose it as a question: How exactly is Review Board supposed to know about ReportsDashboardHook? Like…if we’re rendering the Dashboard, and want to fire off calls to all of our DashboardHooks…how do we do it? How can we find all of the active extension subclasses for DashboardHook?

One way you could do it, is to dive into the extensions directories, and use regular expressions to find defined classes. That sounds like a lot of work, brittle, and prone to error. What else?

Next, you could go back to those extension files, “eval” them (shudder), and extract the globals(), looking for ExtensionHook subclasses. That also sounds like lots of work, brittle, and prone to error.

You could go for class.__subclasses__…but this gives you every subclass, and we just want the hooks that are for active extensions. We could filter out all of the ones that aren’t activated, but we’d have to do that for every hook, and that blows.

Next, we could have developers add their hooks to a registry after defining them. So, we could have:

class ReportsDashboardHook(ExtensionHook): # ... # code goes here # ... dashboard_hook_list.append(ReportsDashboardHook)

And then when an extension is shut down, we just remove it from the global hook list. That doesn’t look so bad, does it? The only problem, is now we have to trust that extension developers will know to add those hooks to the global_hook_list? It’s another step, another thing to forget, and another point of failure.

And it seems silly – I mean, why go through all this effort? Review Board has already seen these hooks…why should it be so hard to just access the list activated hooks easily?

And there it is. That’s why I think we’re using metaclasses.

If you go back to ExtensionHook and ExtensionHookPoint, you’ll notice that ExtensionHookPoint has a list as an instance variable called hooks. That’s the global hook list for that class of hook (DashboardHook). And then ExtensionHook, in its constructor, automatically adds itself to the Extension’s internal list of hooks, as well as the global hook list, with the add_hook method. Shutting down the hook removes that hook from the global hook list.

So now, all we need to do to add our implemented hook to the list of hooks, is to simply subclass DashboardHook, or NavigationBarHook, or any of those Review Board hooks. No need to add the hook to the global list manually – Djblets / Review Board will take care of it. So now, we can get all of the DashboardHook subclasses for activated hooks, easily and consistently, with no extra work for the extension developer. Same with the NavigationBarHook subclasses.

Smooth as glass. Nice.

Anyhow, that’s my understanding of it. If I’m totally off, I’ll let you know when I find out.