So this summer, I’m working on Review Board for the Google Summer of Code.

Until my GSoC acceptance, my romps into the code had been relatively shallow. But with my proposal being given the green light, I’ve started doing more extensive explorations.

Review Board is built using the Django web framework. I haven’t worked with Django before, but I have quite a bit of experience with Rails, so that should be an asset. Using a web framework means having (relatively) predictable source code layout, and Review Board is no exception.

Djblets

At one point or another, the Review Board developers realized that a lot of their code wasn’t Review Board specific, and could be abstracted out into an external library.

That library is called Djblets.

Among other things, Djblets adds a DataGrid component for easy record sorting and pagination. There are improvements to Django’s Authentication system. Functions for easily displaying a user’s Gravatar.

And, low and behold, there is a branch of Djblets that provides classes and functions for giving a Django application an extension framework. The classes are abstract enough so that, in your Django application, you can specify different types and behaviours for your Hooks.

Djblets -> Review Board

The Review Board extension branch takes these Djblets extension classes, and extends them into DashboardHooks, NavigationBarHooks, ReviewRequestDetailHooks…lots of different hooks.

So, Djblets creates the foundation abstractions. Review Board makes these abstractions a little more specific. And then an extension writer needs to instantiate and use these classes to design their extensions. It sounds complicated, I know.

So Let’s Map It Out

When I start learning a new code base, I do a lot of drawing. To me, getting to now a code base is like getting to know a city, and that means walking around it, and mapping it out.

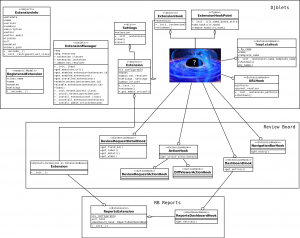

So I’ve taken the liberty of mapping out the extension classes that I’ve found, and how they relate to one another. Note that at the bottom of my map, a simple extension (RB Reports) is using some of those classes to hook itself into Review Board. You can find this, and other extensions,here.

Now, before someone in the department starts complaining about my misuse of UML: I’m not a UML guy. I just wanted an easy piece of diagramming software, and the one that I found (Dia), did UML. I just wanted something to draw boxes and lines. So please don’t freak out if you think I’m using the wrong symbols.

One symbol you might be wondering about is the blue quantum-flux-capacitor-implosion.

I’ll save that for a future post.