Before I start diving into results, I’m just going to recap my experiment so we’re all up to speed.

I’ll try to keep it short, sweet, and punchy – but remember, this is a couple of months of work right here.

Ready? Here we go.

What I was looking for

A quick refresher on what code review is

Code review is like the software industry equivalent of a taste test. A developer makes a change to a piece of software, puts that change up for review, and a few reviewers take a look at that change to make sure it’s up to snuff. If some issues are found during the course of the review, the developer can go back and make revisions. Once the reviewers give it the thumbs up, the change is put into the software.

That’s an oversimplified description of code review, but it’ll do for now.

So what?

What’s important is to know that it works. Jason Cohen showed that code review reduces the number of defects that enter the final software product. That’s great!

But there are some other cool advantages to doing code review as well.

- It helps to train up new hires. They can lurk during reviews to see how more experienced developers look at the code. They get to see what’s happening in other parts of the software. They get their code reviewed, which means direct, applicable feedback. All good things.

- It helps to clean and homogenize the code. Since the code will be seen by their peers, developers are generally compelled to not put up “embarrassing” code (or, if they do, to at least try to explain why they did). Code review is a great way to compel developers to keep their code readable and consistent.

- It helps to spread knowledge and good practices around the team. New hires aren’t the only ones to benefit from code reviews. There’s always something you can learn from another developer, and code review is where that will happen. And I believe this is true not just for those who receive the reviews, but also for those who perform the reviews.

That last one is important. Code review sounds like an excellent teaching tool.

So why isn’t code review part of the standard undergraduate computer science education? Greg and I hypothesized that the reason that code review isn’t taught is because we don’t know how to teach it.

I’ll quote myself:

What if peer code review isn’t taught in undergraduate courses because we just don’t know how to teach it? We don’t know how to fit it in to a curriculum that’s already packed to the brim. We don’t know how to get students to take it seriously. We don’t know if there’s pedagogical value, let alone how to show such value to the students.

The idea

Inspired by work by Joordens and Pare, Greg and I developed an approach to teaching code review that integrates itself nicely into the current curriculum.

Here’s the basic idea:

Suppose we have a computer programming class. Also suppose that after each assignment, each student is randomly presented with anonymized assignment submissions from some of their peers. Students will then be asked to anonymously peer grade these assignment submissions.

Now, before you go howling your head off about the inadequacy / incompetence of student markers, or the PeerScholar debacle, read this next paragraph, because there’s a twist.

The assignment submissions will still be marked by TA’s as usual. The grades that a student receives from her peers will not directly affect her mark. Instead, the student is graded based on how well they graded their peers. The peer reviews that a student completes will be compared with the grades that the TA’s delivered. The closer a student is to the TA, the better the mark they get on their “peer grading” component (which is distinct from the mark they receive for their programming assignment).

Now, granted, the idea still needs some fleshing out, but already, we’ve got some questions that need answering:

- Joordens and Pare showed that for short written assignments, you need about 5 peer reviews to predict the mark that the TA will give. Is this also true for computer programming assignments?

- Grading students based on how much their peer grading matches TA grading assumes that the TA is an infallible point of reference. How often to TA’s disagree amongst themselves?

- Would peer grading like this actually make students better programmers? Is there a significant difference in the quality of their programming after they perform the grading?

- What would students think of peer grading computer programming assignments? How would they feel about it?

So those were my questions.

How I went about looking for the answers

Here’s the design of the experiment in a nutshell:

Writing phase

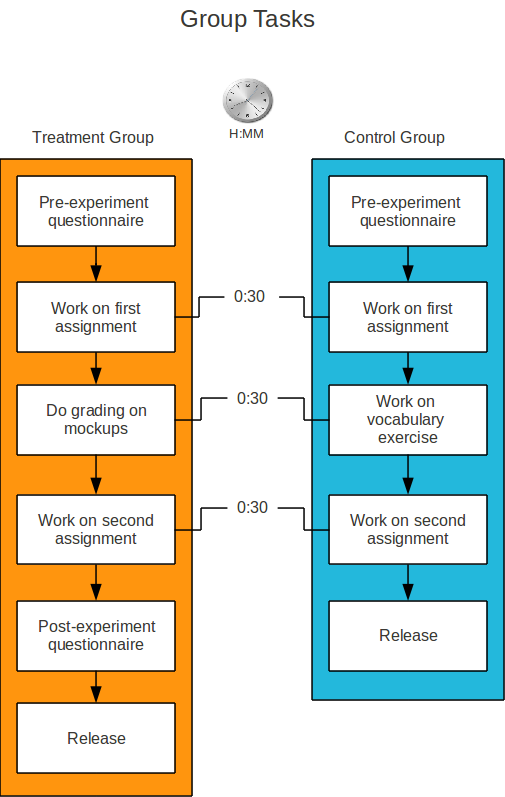

I have a treatment group, and a control group. Both groups are composed of undergraduate students. After writing a short pre-experiment questionnaire, participants in both groups will have half an hour to work on a short programming assignment. The treatment group will then have another half an hour to peer grade some submissions for the assignment they just wrote. The submissions that they mark will be mocked up by me, and will be the same for each participant in the treatment group. The control group will not perform any grading – instead, they will do an unrelated vocabulary exercise for the same amount of time. Then, participants in either group will have another half an hour to work on the second short programming assignment. Participants in my treatment group will write a short post-experiment questionnaire to get their impressions on their peer grading experience. Then the participants are released.

Here’s a picture to help you visualize what you just read.

So now I’ve got two piles of submissions – one for each assignment, 60 submissions in total. I add my mock-ups to each pile. That means 35 submissions in each pile, and 70 submissions in total.

Marking phase

I assign ID numbers to each submission, shuffle them up, and hand them off to some graduate level TA’s that I hired. The TA’s will grade each assignment using the same marking rubric that the treatment group used to peer grade. They will not know if they are grading a treatment group submission, a control group submission, or a mock-up.

Choosing phase

After the grading is completed, I remove the mock-ups, and pair up submissions in both piles based on who wrote it. So now I’ve got 30 pairs of submissions: one for each student. I then ask my graders to look at each pair, knowing that they’re both written by the same student, and to choose which one they think is better coded, and to rate and describe the difference (if any) between the two. This is an attempt to catch possible improvements in the treatment group’s code that might not be captured in the marking rubric.

So that’s what I did

So everything you’ve just read is what I’ve just finished doing.

Once the submissions are marked, I’ll analyze the marks for the following:

- Comparing the two groups, is there any significant improvement in the marks from the first assignment to the second in the treatment group?

- If there was an improvement, on which criteria? And how much of an improvement?

- How did the students do at grading my mock-ups? How similar were their peer grades to what the TAs gave?

- How much did my two graders agree with one another?

- During the choosing phase, did my graders tend to choose the second assignment over the first assignment more often for the treatment group?

Ok, so that’s where I’m at. Stay tuned for results.